The Arrival of the First Africans in Virginia – 1619

How do we begin to understand our true history? The answers lay somewhere within our most troubled past. From America’s birth, much of our history was shrouded by lies and deceit and told and re-told by those in control with the power to meld a falsity to benefit their cause.

How do I know this? After countless hours of research, the physical documents tell a much different story than previously known to the masses, and that of which continues to be told today. TO BE CLEAR… Most of what has been written to date about the arrival of the first Africans in Virginia is incorrect. The problem – previous historians only reviewed the records in Virginia. However, after studying the archives in Bermuda, Spain, England, Japan, Mexico, and Jamaica a broader story emerges.

Where were they from?

From the Atlantic Ocean, narrow coastal cliffs ascend over four thousand feet to a vast plateau extending into the central region of Western Africa, wherein 1619 the Bantu-speaking Kingdom of Ndongo was located, modern-day Angola. Across the immense highlands were small livestock-producing villages and to the eastern interior the Ndongo Kingdom capital of Kabasa – a grand city of artisans, bustling with merchants from near and far selling their commodities in Kabasa’s international market, which rivaled the silk and spice markets of the Far East. In early 1619, the Portuguese contracted with the Imbangala, an African contraband tribe of mercenaries – reportedly cannibals, to raid the Ndongo Capital of Kabasa. Regardless of status, the Imbangala bound and beat their captives, and force-marched them to the Port of Luanda where they were sold as slaves.

Important Note: Because it was an “international market,” we CAN’T assume ALL of these earliest Africans were from the Kingdom of Ndongo. Merchants from the northern Kingdoms of Kongo and Loango were also in the market selling their goods. For example, an African found in the earliest census records is Anthony, who took the last name, Longo. No doubt an acknowledgment of his homeland.

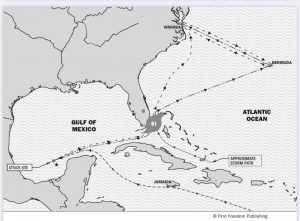

Thirty-six ships left the Port of Luanda in the Spring/Summer of 1619 with full underbellies of enslaved African captives. Of these thirty-six ships, only six sailed to the Spanish Port of Veracruz, New Spain, modern-day Mexico. Of these six ships, only one would report piracy, the captain of the San Juan Bautista.

When the San Juan Bautista left Luanda with a full underbelly, Don Manuel Mendez de Acuna had captained the Spanish ship for less than a year. With 350 bound Africans and an ample crew, the Spanish galleon was heavily burdened. The galleon type was not built to carry human cargo, and the quarters were unusually tight. Within no time, much of the Bautista’s enslaved were ravaged by the harsh conditions of the journey. Inevitably, filth and dysentery took hold, and sickness soon threatened the San Juan Bautista’s entire haul. After sailing nearly fifty-six hundred miles and with the loss of one-third of his cargo, Captain Mendez de Acuna decided he could sail no further. He made port in Jamaica for medicine and enough supplies to sustain his withered cargo to their destination. The treatment and provisions didn’t come cheap as the Spanish captain exchanged twenty-four African boys in trade, before setting sail on the final leg of his journey – an additional thirteen hundred miles to the Spanish port of Veracruz, New Spain.

From the Jamaican port, the San Juan Bautista headed west-northwest. After weeks of travel and within miles of its destination, in the early hours of the morning with a heavy fog lingering beneath the dark rain clouds, the thunder of a cannon was heard. Two English warships fired upon a stagnant Spanish galleon. Under normal circumstances, a Spanish galleon carried adequate defenses to protect the Crown jewels and important documentation it transported to and from the Spanish mainland. A Spanish galleon was high on the list of targets for any privateer, and this galleon, albeit with a full underbelly of enslaved Africans, was ripe for the taking. Roaming the seas for weeks, the Treasurer and White Lion had finally found their prey. The galleon, operating as a slaver, was caught defenseless just miles from its destination of Veracruz.

In the summer of 1619, in the Bay of Campeche off the coast of Veracruz, piracy was committed. Unbeknownst to all involved, this single act of piracy would alter the New World forever. After the initial assault and with the imminent threat of an overtaking, the Spanish captain quickly surrendered. As the two captains boarded the galleon, Captain Mendez de Acuna quickly declared what remained of the cargo he had purchased in the port of Luanda. In disbelief of his declaration, the privateers took hold of the ship, pushing off the captain and his crew in a pinnace, and descended into the underbelly of the Bautista. Consumed by the gaseous stench, they found nothing more than the enslaved Africans the captain had declared. The two English captains, in need of realizing some type of treasure, chose sixty of the healthiest captives. After ample discussion, the decision was made to sail for Virginia, where they believed they would find a safe haven.

As they rounded the coast of Spanish La Florida, the two ships, the Treasurer and the White Lion sailed north into rougher seas. From the south came a mighty storm with damaging wind and heavy rains, which firmly challenged the vessels. When the winds subsided, and the sea calmed, the While Lion had managed to prevail, while the damaged Treasurer floundered behind, and one had lost the other.

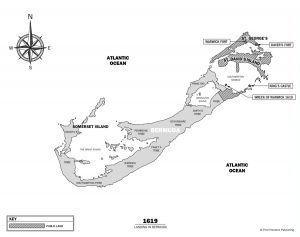

Running from the storm, the White Lion was blown off course. With the experience of her pilot, the White Lion turned northward, where he knew they would sail upon the Somerset at the South-west tip of Bermuda, and where they anchored. Concerned with the dire condition of the famished Africans, the White Lion’s captain decided to send four of his crewmen along with the two of the Africans inland to see if they could find relief. With no word from his crew, each passing hour would have lingered like days. Finally, the word came: It was reported they offered 14 of the Africans aboard in exchange for enough victual for the White Lion to sail on to Virginia. Subsequently, the White Lion’s crewmen, along with the Africans, were detained, and their request to enter the harbor denied. Under a fit of rage, the captain announced, “he would just as soon throw the Africans overboard” than watch them wither.

When the White Lion left Bermuda under duress, the ship must have met the Englishman Kirby. Kendall, the interim Governor of Bermuda, entered into the record – he had traded the Englishman Kirby the Company’s on-hand corn for 14 Africans “he found floating upon the seas.” Whether the White Lion’s captain traded the Governor the Africans for victual, or the Governor purchased them from Kirby, we may never know.

Facts: On August 12, 1619, an English ship carrying a Dutch marque is documented in Bermuda, discussing the piracy of a Spanish galleon of which their African captives were pillaged. Along with the confession was the acknowledgment of the White Lion’s consort, the Earl of Warwick’s privateer, the Treasurer. Within two years, Kendall would file suit against the Earl of Warwick in the English courts – demanding his 14 Africans.

On August 25, 1619, the White Lion glided into Old Point Comfort and dropped anchor. The Port commander, William Tucker, climbed aboard, and the English captain Jope declared his cargo under his Dutch marque of Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange. Jope proclaimed he fell in consort with the Treasurer in the West Indies, with whom he took the poor souls from a faltered Spanish ship in the Bay of Campeche. When Commander Tucker questioned Jope as to the whereabouts of the Treasurer, Jope explained how he lost the Treasurer in the storm. Because of Jope’s Dutch marque, he was welcomed into the settlement, and the balance of the Africans (14) were traded to the governor and cape merchant for food.

On August 25, 1619, the White Lion glided into Old Point Comfort and dropped anchor. The Port commander, William Tucker, climbed aboard, and the English captain Jope declared his cargo under his Dutch marque of Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange. Jope proclaimed he fell in consort with the Treasurer in the West Indies, with whom he took the poor souls from a faltered Spanish ship in the Bay of Campeche. When Commander Tucker questioned Jope as to the whereabouts of the Treasurer, Jope explained how he lost the Treasurer in the storm. Because of Jope’s Dutch marque, he was welcomed into the settlement, and the balance of the Africans (14) were traded to the governor and cape merchant for food.

The Treasurer arrived within a few days, and Captain Elfrith found the fate had dealt him a short-hand. When he landed at the mouth of the James River, Commander Tucker came aboard, and Elfrith declared his cargo under the Italian marque of the Duke of Savoy. Tucker advised Elfrith that his Duke of Savoy’s marque had expired, and permission from the Governor in Jamestown was necessary to allow him to disembark and sell his cargo. Promptly, the commander sent word to the newly appointed Governor Yeardley in Jamestown of the Treasurer’s arrival.

Unbeknownst to Captain Elfrith and the Treasurer’s owners, with undaunting determination to stifle the pirating in Virginia, Edwin Sandys, the newly elected Virginia Treasurer, had sent a warrant to the Governor. The warrant contained orders to detain the Treasurer should the ship return to Virginia. The Governor sent two of his men, Lt. William Pierce and William Ewens, to Old Point Comfort to escort the Treasurer back to Jamestown. Once the Governor’s men arrived at Point Comfort, they reported back that they only saw her sails as the Treasurer disappeared into the Chesapeake.

Note: If the 60 Africans taken from the San Juan Bautista were split equally between the White Lion and the Treasurer – only 14 would have been left on the White Lion when she arrived on August 25.

30 Africans, less the 14 traded in Bermuda, and the 2 detained, would leave 14.

When the Treasurer left Virginia, she sailed for Bermuda, where Captain Elfrith believed he might find protection through the Treasurer’s owner, the Earl of Warwick. Warwick’s deep pockets had allowed for a web of allies looking after his interest not only in Virginia but in Bermuda as well.

The White Lion’s captain Jope and pilot, Marmaduke Rayner, remained in Virginia until after the end of September, when they sailed for England, no doubt stopping in Bermuda to regain his crew and the two Africans, all along with correspondence from the Governor’s personal secretary, who referenced the escapades of the so-called Flemish ship.

At the same time the White Lion sailed from Virginia, the Treasurer was arriving in Bermuda. Her condition was noted as “so weather-beaten and tourne, as never like to put to sea again, but lay her bones here.” Upon the Treasurer’s arrival, Captain Daniel Elfrith declared his cargo.

29 Africans, 2 chests of graine, 2 chests of wax, and a smale quantity of tallow.

The Africans purchased in Luanda and put aboard the Treasurer in the Bay of Campeche had now traveled an additional two-thousand miles. After more than ten thousand total nautical miles, their condition was very poor at best.

In Virginia, fate had dealt Elfrith’s hand; Bermuda would be no different. Bermuda’s governor, like Virginia’s governor, had changed since Elfrith last anchored. In the early summer of 1619, when Elfrith headed out from Bermuda to roam and pilfer in the West Indies, Governor Daniel Tucker was in command. Called to England to argue a case, Governor Tucker reluctantly left Lieutenant Governor Miles Kendall in charge.

Arriving simultaneously in Bermuda with the Treasurer, was Tucker’s replacement, the newly elected governor, Captain Nathaniel Butler, eager to take over his post. But, before Butler could take his seat, Kendall had allowed the Treasurer to unload its maritime contraband. However, due to the Duke of Savoy’s expired marque, the Africans were placed in the longhouse on the company’s public lands until the legalities could be worked out.

It’s interesting… the first letter regarding the arrival of Africans was penned January 1620, several months after their arrival. The author was John Rolfe, the secretary of the Virginia Company. The words he wrote were part of a grand scheme, concocted to save the head of a powerful English earl, Robert Rich, II Earl of Warwick. Rolfe claimed a Dutch ship brought nothing but “20 and odd negroes.”

Why???

THEY DIDN’T ALL ARRIVE ON THE WHITE LION ON AUGUST 25, 1619.

Let us acknowledge the Africans who arrived in Virginia in February of 1620.

Who were they?

They too were from the Spanish slaver, the San Juan Bautista, pirated in the Bay of Campeche in the summer of 1619. Like the Africans who arrived on the White Lion, they were put aboard the Treasurer and brought to Virginia arriving on August 29th, 1619.

Warned off, or so it seemed, the Treasurer abruptly disappeared from Point Comfort sailing for Bermuda. Upon arriving in Bermuda, 29 Africans were documented going ashore and being detained in the “longhouse.” Sometime in February of 1620 approx. 18 Africans returned to Virginia. These Africans suffered one of the longest middle passages of record. Making the total number of San Juan Bautista Africans documented in Virginia by March of 1620 was 32.

Click the link to listen to K I Knight tell their story. https://vahistorypodcast.com/tag/k-i-knight/