The realization of my husband’s unknown ancestry becomes my quest, ‘To find the stories of his Ancestors past’. He has very little information about who they were or where they came from, so I dig in hard to see what I can find. It becomes like a hidden treasure map to me, soon finding one then the next with many of the men in his direct paternal line being men of elevated standing during their time. One is the youngest state attorney ever appointed, another a senator, the next a war hero-if I may, who his opponent could never hold, but one in the same as the Lieutenant who lost several cousins riding with him in Florida’s First Calvary. Proudly reporting back to my husband, with one find then the next, I easily go back several generations, finding more and more. The hunt becomes an addiction. Who or what will I find next?

For Christmas of 2007, we give my father in-law a family tree of his direct paternal lineage going back to the 1600’s, and in return I receive the best gift I could ask for. Not a gift as a package would be, but a request to find a new story. My father in-law wants to know about the Minorcan heritage he always heard of through his grandmother’s line, the Senator’s wife, who became the third female to take and pass the Florida bar.

Her name is Nancy L. Langford, born September 22, 1879, Bradford County, Florida. Her father John Alexander Langford, born Columbia County, Florida November 26, 1837. Her mother, Nancy Alice Roberts, born in 1844. I continue up the maternal line with Roberts leading me to John J. Roberts her father and Sarah “Sallie” Sweat, her mother, the beginning of a new line to explore, the Sweats.

Buried not far from where we currently live on old family property, we go to the cemetery and find their graves. The question of the Minorcan heritage again surfaces. Could Sallie Sweat be of Minorcan descent?

Maybe it was pronounced Sweet? Sweat could be Sweet I thought. In genealogy we find there can be many variations in a single generation, depending on who records the entry. Not far to our east is St. Augustine, where many Minorcans lived in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s, when Florida was a Spanish Territory. Could it be so simple?

As a genealogist, we search for facts that can be supported by records or documents such as birth records, a last will and testament, a census, tax and land records and even the local telegraph. With a very clear documented history, Sarah “Sallie” Sweat’s father is John Sweat, born c. 1794 Burke, Bulloch County, Georgia (Pioneers of Wiregrass, 1850 Columbia County, Florida Federal Census.) John Sweat married Charlotte Moore, (Pioneers of Wiregrass.; and then I find them in 1850 Columbia County, Florida (Federal Census). John Sweat dies in 1868, New River County, which is now known as Bradford County, Florida. John served in the Indian Wars as a private in Captain Jonathan Knight’s company of Lowndes County Militia, 1840. (Pioneers of Wiregrass) Is this another clue? Jonathan Knight is my husband’s fourth generation direct paternal great grandfather. Soon after arriving in Florida, John Sweat served as a Justice of the Peace in Columbia County, Florida from 1845 to 1847 (source: Pioneers of Wiregrass.)

Further, I trace back another generation to Nathan (sometimes written Nathaniel) Sweat, R.S., born between c.1753-1760 of Marion District, South Carolina. Nathan is listed in Captain Robert Lide’s Company of Volunteer Militia who signed a petition to the Council of Safety of South Carolina on 9 October 1775. He was counted as white in 1790, head of a Beaufort District, South Carolina, a household of one white male over 16, one white male under 16, and four white females [SC:11]. Next I find another reference to a Nathan Sweat in a book by Genealogist/Historian Paul Heinegg, called “Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina.”

Free African Americans? But Nathan Sweat, R.S. is listed as white in the census of 1790 Beaufort, SC. Is this the same Sweat family?

Looking in the Georgia Black Book, I find on page 90 a Nathan Sweat, son of Nathan Sweat (R.S.) being arrested and gives his physical description.

Sweat, Nathan – Cattle Stealing, 7 Jan 1836 Appling Co., Farmer Georgia 39 yrs., 6’2″

Dark complexion, dark hair, dark eyes. He is pardoned 30 Nov 1837.

John’s father Nathan had at least seven children, and one was named Nathan, Jr. With my interest now peeked, my search intensifies. According to the Reverend Alexander Gregg, Rector of St. David’s Church in Cheraw, South Carolina, William was the father of Nathan, James and William Sweat. [Gregg, History of the Old Cheraws, 101, 311, 312]. William Sweat marries Lucy Turbeville/Turbevil, c. 1750, South Carolina. Reverend Gregg’s account also lists William Sweat as a Mulatto/Melungeon.

Until this point, every census has listed their race as White. I now realize the Sweat line is not of a Minorcan heritage at all, it is documented to be Melungeon.

Melungeon-(pron.) is a term traditionally applied to one of a number of tri-racial isolate groups.

Tri-racial-(pron.) describes populations thought to be of mixed European, sub Saharan African and Native American Ancestry.

On 23 July 1763 William Sweat is named as executor and son-in-law of John Turbeville who mentions his daughter Lucy Sweat and grandson Nathan Sweat in his Craven County, South Carolina will (which was proved 3 August the same year.) [WB RR: 55]. On the 16th July, 1772, William receives a grant of 150 acres on Three Creeks in Craven County, Beaufort District of South Carolina. William Sweat dies 23 Jul 1783, in Hunt’s Bluff, Cheraw District, Chesterfield, SC. He becomes known as William Sweat of Hunt’s Bluff.

Who is William Sweat of Old Cheraw? His father was also named William Sweat. He was born in 1690, Surry County, Virginia. Surry County…….this is a new clue. Note: Part of James City County, VA became Surry County, VA.

Next a simple google.com search sends me into a tale-spin!

From the Minutes of the Governor’s Council.

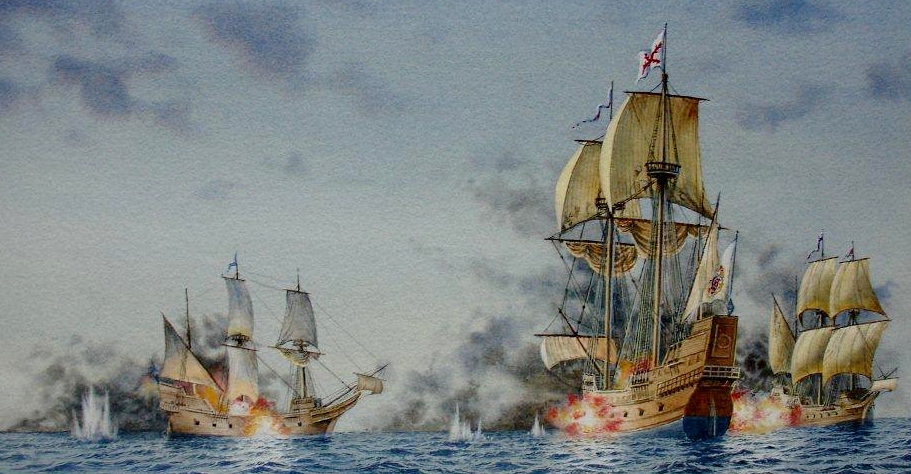

17 October 1640: James City Court: “Whereas Robert Sweat hath begotten with child a negro woman servant belonging unto Lieutenant Sheppard, the court hath therefore ordered that the said negro woman shall be whipt at the whipping post and the said Sweat shall tomorrow in the forenoon do public penance for his offence at James City church in the time of divine service according to the laws of England in that case provided.” [Virginia Council and General Court Records 1640-1641, in “Virginia Magazine of History” Vol. II, p. 281] This was a general law against fornication that applied to all members of the colony. Note that she was a servant and not a slave.

Within six months, she again is brought before the court, but this time by her husband.

March 31, 1641-Suit of John Gowen;

“Whereas it appeareth to the court that John Gowen, being a negro servant

unto William Evans, was permitted by his said master to keep hogs and make

the best benefit thereof to himself provided that the said Evans might have

half the increase which was accordingly rendered unto him by the said negro

and the other half reserved for his own benefit: And whereas the said negro

having a young child of a negro woman belonging to Lt. Robert Sheppard which

he desired should be made a Christian and be taught and exercised in the

church of England, by reason whereof he, the said negro did for his said

child purchase its freedom of Lt. Sheppard with the good liking and consent

of Tho: Gooman’s overseer as by the deposition of the said Sheppard and Ewens

appeareth, the court hath therefore ordered that the child shall be free from

the said Evans or his assigns and to be and remain at the disposing and

education of the said Gowen and the child’s godfather who undertaketh to see

it brought up in the Christian religion as aforesaid.”

My heart sinks. Who is this woman? What is her story? How did she find herself in such a situation?

Subscribe to my blog and continue to read my discovery of her story.