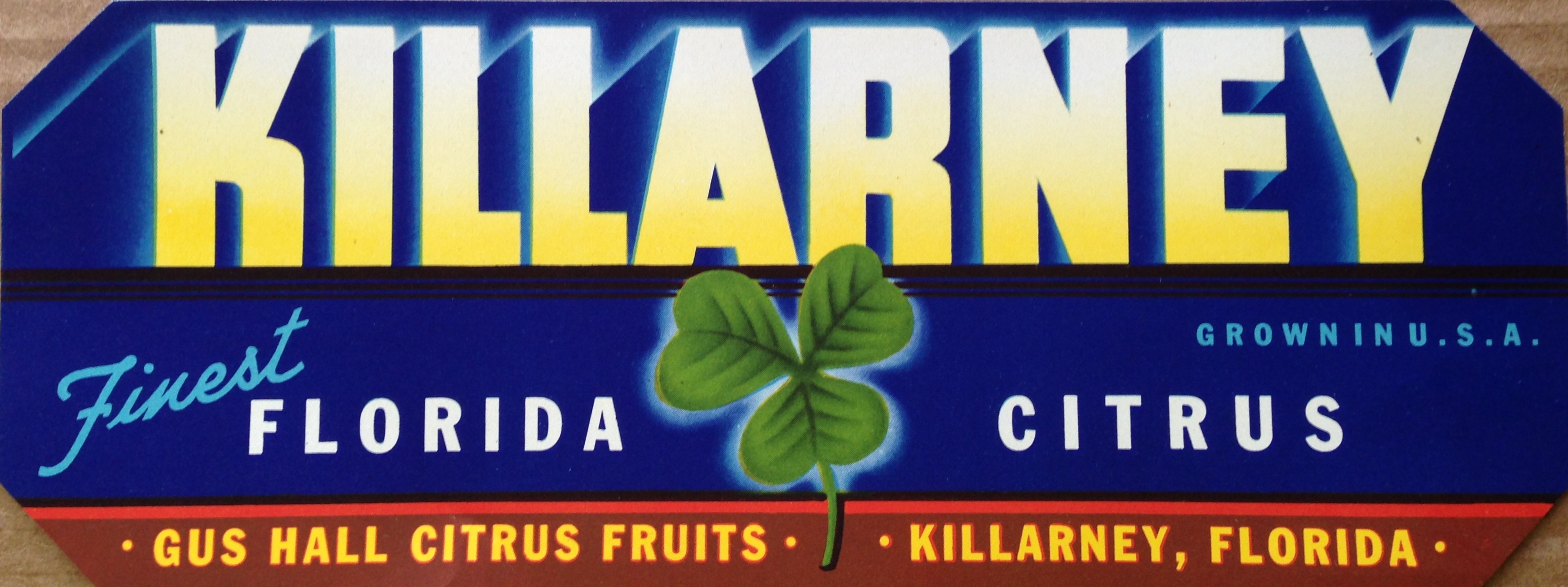

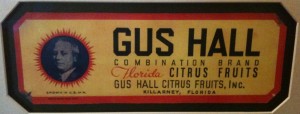

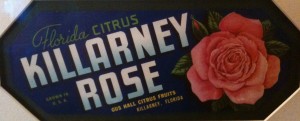

Gus Hall Citrus Fruits

Gus Hall (1881-1956) began his long tenure in the citrus industry when he joined the South Lake Apopka Citrus Growers Association as General Manager in 1910. Under his leadership, South Lake grew from humble beginnings to an operation handling 641,000 boxes of fruit annually. One of Hall’s successful innovations while at South Lake involved featuring his face on the Gus Hall Combination Brand crate label, making him instantly recognizable while attending industry events in northern markets. After 31 years with South Lake Apopka Citrus Growers Association, Hall left to form his own operation, Gus Hall Citrus Fruits. His packing house, located just west of Oakland in Killarney, was constructed by T&G Railroad on State Highway 438. From South Lake, he brought his Gus Hall brand label and added other labels including Boxcar and GH. In 1946, he sold his interest in the company, and it was renamed Killarney Fruit Company.

The Great Massacre of 1622

The day would be like no other yet it started as every other had. The fields were active and the town was a bustle with merchants trading up and down the river as the natives began to arrive with their own trade. Then, like a bell tolling out, the natives turn savage mutilating one unsuspecting settler then the next. Bodies are strewn about, with no pause for woman or child. They all lay tangled, one with another, hacked and disfigured.

When the savagery calms and the tallies are made, some three hundred forty-seven souls are lost, a third of the struggling settlement’s total population. Of the eighty (80) plantations that were beginning to flourish up and down the James River, they all lay in wait, now gathered within eight (8) to sustain a position of defense.

General Muster of Virginia 1619/1620

Historians have long believed that the earliest documented Africans to arrive on American soil were brought in August of 1619, courtesy of a Dutch Captain. The evidence was confirmed in the earliest known count of the inhabitants of Virginia, known as the ‘List of the Living’, compiled after the Great Massacre of 1622. However, in the last decade, new discoveries have been made and some Historians now believe there was an earlier notation. Found in the Ferrar papers, the two page “General Muster of Virginia” dated March 1619 lists, at the bottom of the second page, thirty-two (32) Africans. Assuming that those same 32 Africans were there five months later when the “twenty and odd” arrive, there would have been no less than 53 Africans. The “List of the Living” completed after the Indian massacre of 1622 indicates that there were 23 Africans at that time. Historical records indicate that no Africans were killed in the 1622 massacre. That means that no less than 30 Africans died between August 1619 and 1622. Very unlikely. If this were the case, where would the 32 Africans have come from? How did they arrive? There are no records that indicate the arrival of any Africans prior to August of 1619 from England. If not England, where? In 1619, Virginia was an English settlement and all inhabitants were from England, with the exception of the occasional Frenchman or Italian.

Since the discovery of the Ferrar Papers, Martha W. McCartney proposed that the March 1619 muster was written in the old-style which dates it to 1620. Therefore, if the Muster was completed in 1620, the number of Africans jumped from ‘twenty and odd’ to 32 in less than a year?” The answer to this question could fall within Dutton’s letters from Bermuda. When the Treasurer arrived in Bermuda it was noted to be carrying 29 Africans. Dutton reveals Gov. Miles Kendall only receiving 14 of these Africans. It has been suggested by Historians Heywood & Thornton the balance of the Africans (approx. 15) returned on the Treasurer back to Virginia.

My Opinion: Many possibilities exist! I feel the 23 Africans that are listed on the “List of the Living” are the same Africans that arrived in August 1619 on the White Lion. They were the first Africans to arrive at the English settlement of Virginia. There were none before them. The 32 Africans listed on the March 1619/1620 General Muster of Virginia could have existed. Hidden away in the Farrar papers, they became part of a scheme concocted to cover the tracks of piracy by an English aristocrat and his cronies.

Fate & Freedom

Discovering Margaret…..

Twenty and Odd Africans arrive in Virginia in 1619. Most of their names are unknown, or quite possibly they were concealed. The less known about the incident would be best. The names we have are from the ‘List of the Living’ compiled after the Indian massacre of 1622. They were Angela, Anthony, Isabel, Frances, Peter, Anthony, and Margaret. The others were identified as only male or female as much about the whole incident would be camouflaged to protect the few involved.

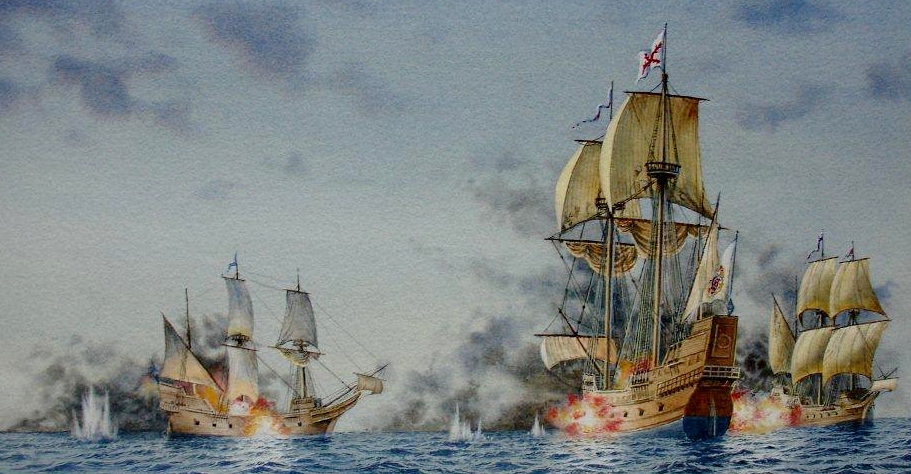

Documents show that the Africans arrived at Old Pointe Comfort, Virginia in the later part of August, 1619. The Captain, a former Calvinist Reverend turned Privateer, reported his only cargo as being “Twenty and Odd” Africans he took (pirated) from a floundering vessel off the coast of Vera Cruz, Mexico. Under the watchful eye of the crown the incident is quietly reported. John Pory, the Virginia Company’s newly appointed Secretary, writes in a letter to Sir Dudley Carleton dated September 30, 1619,

“Having mett with so fitt a messenger as this man of Warre of Flushing.” The letter goes on to tell of the arrival of some “twenty and odd” Africans brought by a Dutch Captain.

Was Pory disguising the ship to protect its captain and crew? Probably not.

Oddly, the letter was sent to Sir Dudley Carleton via messenger, Marmaduke Reynor, the English pilot of the White Lion. This information alone is telling of some sort of an association.

Was Pory’s loyalty to the company, trying to diminish the association by the cover of a Dutch marque? Or was his loyalty to the Earl of Warwick? Possibly it was to the English Crown. But, clearly Pory’s loyalties didn’t align with the White Lion who was sent back into the English channels with a letter suggesting a Spanish piracy, not to mention, a cargo that would confirm Pory’s words.

Why? There are several reasons.

Just months before the African’s arrival, Samuel Argall, the acting Governor of Virginia, was ordered to return to England to face questioning from the King’s Privy Council regarding the suggestion Virginia was nothing more than a Pirate’s haven. The thought of a Spanish Piracy by an English ship so soon might be the last straw to an English King’s already tarnished image with Spain. Proof of a Spanish piracy would surely condemn the Virginia Company, giving King James good reason to revoke their patent.

Another reason…..there were two ships involved, two English Corsairs. When the Treasurer arrived at Pointe Comfort carrying Africans just days after the White Lion, oddly the Treasurer was immediately turned away, or was the ship warned off? The Treasurer, captained by Daniel Elfrith was owned by Robert Rich II, Earl of Warwick, one of the most influential and powerful men in England. The Treasurer would sail for Bermuda, an island known to be under the Earl of Warwick’s hand, where he could control the secrecy of the situation.

England would be tricky, as the White Lion was a common sight in the Port of Plymouth where the ship sat for years. Reverend Jope had purchased the decayed White Lion from a member of his congregation, who captained the ship during the Elizabethan War between England and Spain 1585-1604. In fact, it was the Port of Plymouth where Captain Jope re-launched the White Lion’s sails after the ten (10) years it took to refurbish the old war ship. The White Lion, it’s captain and it’s crew were English, not Dutch as Pory’s letter would suggest and now their identities would need to be hidden under the association of a “Dutch” marque.

As fate would have it, the San Juan Bautista’s Captain Acuna, who reported the incident upon his arrival in Mexico, was kin to Count Gondomar, the Spanish Ambassador who was in the inner circle of England’s King James. When the Spanish Captain Acuna makes claim to his kin that two English Corsairs pirated his San Juan Bautista just off the coast of Vera Cruz, Mexico stealing some fifty or sixty African slaves, Virginia becomes the target of Gondomar’s rage and demands retribution. For an English Captain in the year of 1619 the act of Spanish piracy would be a death sentence, for it was less than two years earlier Sir Walter Raleigh was be-headed for Spanish piracy, a result of Gondomar’s insistence under the Maritime Peace Treaty.

Continue to follow this blog as I reveal my findings while discovering Margaret.

Our Responsibility to our Ancestors Gravesites

Over two years ago, my husband and I relocated to Keystone Heights, Florida, returning to live on family property that was purchased some hundred years earlier by his family. Not long after arriving, and with much persistence on my part, we take a short trip to an old cemetery to locate one of Florida’s First Pioneers. Jonathan Knight, who arrived with his family in Florida in 1843-44 is my husband’s gr. gr. gr. great-grandfather. He settled in the area then known as Black Creek, which is now part of Middleburg.

Upon arriving at the cemetery, I noted its separate cemetery signs with two (2) different names, one being Forman Cemetery, the other Fowler Cemetery. As we looked for his ancestors graves, my first impression was that the cemetery was well maintained. We start our search checking one then the next, reading the names and dates, but finding no success. Frustrated, we begin to leave. As I turn back for one last look, I notice an area in the corner, mounded with leaves, dead limbs, and debris from the other graves (old plastic flowers) that had been discarded. At first glance I thought it was only a trash pile. I walk closer and I notice first one head stone and then another. I walk around to view the names as they are facing away from me. As I read the names, instead of being excited that I had found his ancestors, my heart sinks. One headstone reads Jonathan Knight, the other of his wife, Elizabeth. My emotions erupt as it is devastating to find their graves in such condition.

My first thoughts…..Why was the other part of the cemetery freshly mowed, free of debris, while their graves are among the trash pile? Who would do such a thing?

Appalled and without answers, we schedule a day to return to clean up the area which clearly seemed to be purposefully neglected. We remove the debris, cut down vines as well as hanging limbs from the trees that have grown out of control and rake away the heap of leaves left to rot on top of the graves. After several hours of work, the area looks like a gravesite once more, instead of the trash pile that we found. For several months, I revisit the cemetery often finding it much as we left it, neat and without debris, yet I still wonder why their gravesite had been left in such conditions.

Within the next few months I find myself on a mission taking a Cemetery Rehabilitation and Preservation class, and become certified in the laws and practice of preserving historic cemeteries. It included the do’s and don’ts of gravesites and what to use to clean and care for the headstone itself (depending on the era, there were many different types of materials used), the area surrounding the grave, as well as listing the cemetery within the historic registry. After all, it was over a hundred-fifty years ago when Jonathan Knight was buried in Forman Cemetery.

For the next year or so, I continue to return, picking up any debris that might have blown into the corner where the graves were located. Then for several months, I’m unable to return, for one reason or another. But, this past Friday, on my way home from a trip to Orange Park, I’m driving through Middleburg when the resounding thought hits me. “I should take a quick detour to check on the cemetery.” As I arrive, I’m shocked to find debris thrown on top of the Knight graves once again. Large limbs are lying across one, with a sheet of plywood leaning against another, and trash strewn about. I turn to look at the other areas of the cemetery and find it clean, and free of any debris. As I turn back to the Knight graves, once again I’m left disheartened.

WHY WOULD ANYONE DO THIS? I just don’t understand.

Christmas Past

Christmas Customs

An article from The Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter, vol. 16, no. 4, winter of 1995-96 written by Emma L. Powers, a historian in the department of Historical Research at Colonial Williamsburg.

Christmas in colonial Virginia was very different from our twentieth-century celebration. Eighteenth-century customs don’t take long to recount: church, dinner, dancing, some evergreens, visiting–and more and better of these very same for those who could afford more. It’s certainly a short list, I tell myself, as I plan meals, go shopping, bake cookies, write three hundred cards, stuff stockings, and dog-ear or recycle the hundreds of catalogs that begin arriving at my house in October.

Attend church, stick some holly on the window panes, fix a great dinner, go to one party, visit or be visited. It sounds so refreshingly easy and simple and quick. But I’d miss a tree with lots of lights and all my favorite ornaments collected over the years. And if there were only one special meal, how could I hope to eat my fill of turkey and goose, both mince-pie and fruitcake, shrimp as well as oysters? Materialist that I am, I would surely be disappointed if there were no packages to open on the morning of December 25.

Our present Christmas customs derive from a wide array of inspirations, nearly as various and numerous as the immigrants who settled this vast country. Most of the ways Americans celebrate the midwinter holiday came about in the nineteenth century, but we’re extraordinarily attached to our traditions and feel sure that they must be very old and supremely significant. What follows is a capsule history of some of our most loved Christmas customs. Perhaps both residents and visitors will enjoy learning the background of one or more of these rites. I offer them in the spirit of the season: with best wishes for continuing health and happiness to all!

Christmas, a children’s holiday? No eighteenth-century sources highlight the importance of children at Christmastime–or of Christmas to children in particular. For instance, Philip Vickers Fithian’s December 18, 1773, diary entry about exciting holiday events mentions: “the Balls, the Fox-hunts, the fine entertainments. . .” None was meant for kids, and the youngsters were cordially not invited to attend. Sally Cary Fairfax was old enough to keep a journal and old enough to attend a ball at Christmas 1771, so she was not one of the “tiny tots with their eyes all aglow.” The emphasis on Christmas as a magical time for children came about in the nineteenth century. We must thank the Dutch and Germans in particular for centering Christmas in the home and within the family circle.

Gift giving. Williamsburg shopkeepers of the eighteenth century placed ads noting items appropriate as holiday gifts, but New Year’s was as likely a time as December 25 for bestowing gifts. Cash tips, little books, and sweets in small quantities were given by masters or parents to dependents, whether slaves, servants, apprentices, or children. It seems to have worked in only one direction: children and others did not give gifts to their superiors. Gift-giving traditions from several European countries also worked in this one-way fashion; for example, St. Nicholas filled children’s wooden shoes with fruit and candy in both old and New Amsterdam. (Eventually, of course, “stockings hung by the chimney with care” replaced wooden shoes.) We must attribute the exchange of gifts among equals and from dependents to superiors to good old American influences. Both twentieth-century affluence and diligent marketing has made it the norm in the last fifty years or so.

Santa Claus too is an American invention, although an amalgam of American, Dutch, and English traditions: partly the lean, ascetic Saint Nicholas, he is also related to the bacchanalian Father Christmas. While many countries and ethnic groups have a Christmastime gift bringer, the “right jolly old elf” dressed in red and fur and driving his sleigh and reindeer sprang from the pen and imagination of New Yorker Clement Clark Moore. In his 1823 poem “A Visit from Saint Nicholas,” Moore created the new look for the Christmas gift-giver. Cartoonist Thomas Nast completed the vision with his 1860s drawings that still define how we see Santa.

Christmas cards. Printers have been cashing in on Christmas since the eighteenth century–at least in London and other large cities. Schoolboys (and I do mean only the young males) filled in with their best penmanship pages pre-printed with special holiday borders. “Christmas pieces” they were called. But the Christmas card per se was a nineteenth-century English invention.

Garlands and greens. Decorations for the midwinter holidays consisted of whatever natural materials looked attractive at the bleakest time of year–evergreens, berries, forced blossoms–and the necessary candles and fires. In ancient times, Romans celebrated their Saturnalia with displays of lights and hardy greenery formed into wreaths and sprays. Christian churches have long been decorated for Christmas. The tradition goes back so far that no one knows for certain when or where it began.

No early Virginia sources tell us how, or even if, colonists decorated their homes for the holidays, so we must rely on eighteenth-century English prints. Of the precious few–only half a dozen–that show interior Christmas decorations, a large cluster of mistletoe is always the major feature for obvious reasons. Otherwise, plain sprigs of holly or bay fill vases and other containers of all sorts or stand flat against window panes. (I cannot tell for sure how these last were attached; perhaps the stems were merely stuck between the glass and the wooden muntins.)

Christmas trees. If we had to choose the one outstanding symbol of Christmas, of course it must be the gaily decorated evergreen tree with a star at the very top. German in origin, “Tannenbaum”:; gained acceptance in England and the United States only very slowly. The first written reference to a Christmas tree dates from the seventeenth century when a candle-lighted tree astonished residents of Strasbourg. I have found nothing recorded in the eighteenth century about holiday trees in Europe or North America. By the nineteenth century a few of the ” German toys” use Charles Dickens’s phrase) appeared in London. But these foreign oddities were not yet accepted. When a print of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s very domestic circle around a decorated tree at Windsor Castle appeared in the Illustrated London News in 1848, the custom truly caught on.

At about the same time, Charles Minnegerode, a German professor at the College of William and Mary, trimmed a small evergreen to delight the children at the St. George Tucker House. Martha Vandergrift, aged 95, recalled the grand occasion, and her story appeared in the Richmond News Leader on December 25, 1928. Presumably Mrs. Vandergrift remembered the tree and who decorated it more clearly than she did the date. The newspaper gave 1845 as the time, three years after Minnegerode’s arrival in Williamsburg. Perhaps the first Christmas tree cheered the Tucker household as early as 1842.

Christmas foods and beverages. Everyone wants more and better things to eat and drink for a celebration. Finances nearly always control the possibilities. In eighteenth century Virginia, of course, the rich had more on the table at Christmas and on any other day, too, but even the gentry faced limits in winter. December was the right time for slaughtering, so fresh meat of all sorts they had, as well as some seafood. Preserving fruits and vegetables was problematic for a December holiday. Then as now, beef, goose, ham, and turkey counted as holiday favorites; some households also insisted on fish, oysters, mincemeat pies, and brandied peaches. No one dish epitomized the Christmas feast in colonial Virginia.

Wines, brandy, rum punches, and other alcoholic beverages went plentifully around the table on December 25 in well-to-do households. Others had less because they could afford less. Slave owners gave out portions of rum and other liquors to their workers at Christmastime, partly as a holiday treat (one the slaves may have come to expect and even demand) and partly to keep slaves at the home quarter during their few days off work. People with a quantity of alcohol in them were more likely to stay close to home than to run away or travel long distances to visit family.

Length of the Christmas season. Eighteenth-century Anglicans prepared to celebrate the Nativity during Advent, a penitential season in the church’s calendar. December 25, not a movable feast, began a festive season of considerable duration. The twelve days of Christmas lasted until January 6, also called Twelfth Day or Epiphany. Colonial Virginians thought Twelfth Night a good occasion for balls, parties, and weddings. There seems to have been no special notice of New Year’s Eve in colonial days. (Maybe that is to be expected since Times Square was not yet built and Guy Lombardo had not been born.) Most music historians agree that the song “The Twelve Days of Christmas” with all its confusing rigmarole of lords a-leaping and swans a-swimming was meant to teach children their numbers and has no strong holiday connection.

In the late 1990s the Christmas season seems to begin right after Halloween and comes to a screeching halt by Christmas dinner (or with the first tears or first worn-out battery, whichever comes first). We emphasize the build-up, the preparation, the anticipation. Celebrants in the eighteenth century saw Christmas Day itself as only the first day of festivities. Probably because customs then were fewer and preparations simpler, colonial Virginians looked to the twelve days beyond December 25 as a way to extend and more fully savor the most joyful season of the year.

First Thanksgiving

As a student in America’s public school system you are taught “Thanksgiving” began on the shores of Plymouth, in present-day Massachusetts, in the year of 1621. However, historical documents describe an earlier record of a “Day of Thanksgiving” celebrated on the shores of the James River, in 1619 when a group of 38 English settlers arrived at Berkeley Hundred on the North bank of the James River, near Herring Creek in an area then known as Charles Cittie.

On the day of their arrival, December 4, 1619, Captain John Woodleaf held a service of thanksgiving and declared, “Wee ordaine that the day of our ships arrival at the place assigned for plantacon in the land of Virginia shall be yearly and perpetually keept holy as a day of thanksgiving to Almighty God.”

The Charter of Berkeley Plantation specifies that “the first day of its occupants arrival shall be observed yearly as a “day of thanksgiving to God”. Berkley Hundred is located about 20 miles upstream from Jamestown, where the first permanent settlement of Virginia was established on May 14, 1607.

DNA – the ultimate ancestry search

DNA results can even surprise a family historian and professional Genealogist. DNA is a must if you want to discover your TRUE identity. When the Kinfolk Detective receives unexpected DNA results a new search took flight. Surnames which were believed to be English, Irish, and Scottish, are ultimately only Partially European with the balance being Jewish, African, Middle Eastern and Asian.

Hall, Blount, Baker, Davis, Brazel, Moore, Kirkland and Creed are my Paternal surnames and Graves, Witty, Davis, Roberts, Johnson, Erikson, Reaves, and Letson are my Maternal. Now, after receiving these DNA results I will begin a new journey to find the origin of each of the surnames in these four generations. (By the fifth generation the amount of a specific strain would be non-reportable.)

I will begin with my Paternal gr. great grandparents Kirkland and Creed. These surnames are in my fathers maternal line, and his mother’s maternal grandparents. William Kirkland married Angeline Irine Creed in 1875. According to an 1900 census, Born in South Carolina, William Kirkland was 52 years of age. His wife of twenty-five years born in Georgia was 49 years of age and they were residing in Sawdust, Tattnall County, Georgia with ten of their children. My grandmothers, mother was their youngest at the age of one. Lucky for me, my 97-year-old grandmother is living and has a powerful memory. After questioning her, I find she remembers her mother telling her that her grandmother was a North Carolina Cherokee. Could this be a strain I’m looking for?

I search the internet, looking specifically for South Asian DNA with the population being Southeast Indian, North Indian and Middle Eastern DNA with the population being from Bedouin, and Mozabite. I find there are several suggestions of North Carolina Cherokee Indian. Could this be the link? After a Google search with the keywords Kirkland and North Carolina Indian, I find Nathan Kirkland “Cheesequire” who was a Cherokee Indian chief who lived to be 135 years of age reported to have descendants living in Edgefield, SC, where William Kirkland was born. Could this be a clue? Could William Kirkland be of North Carolina Cherokee descent?

Continue to follow under my “exploring DNA” category.